This happy occasion is brought about by the imaginative and valuable program of the Whiting Foundation in support of writers, and therefore in support of literature. They have undertaken, in my view, a very difficult task, which is of discovering talent and promise in beginning writers. This discovery is much more anxious-making than acknowledging what others have discovered. However, they have acknowledged well, as you can tell tonight. Some of the writers have published a number of books, some have published one, and some have published none, so this shows the wonderful courage of the foundation. Also, I wish to speak of the gallantry of the money, which I suppose won’t change anyone’s life, but it might change the next year or two. As for this program, I can’t think of any other so fraught with bureaucratic pains of process, so rich in rewards.

I thought I would speak briefly about reading and readers. I’m aware that I can take a very out- of-date, provincial point of view because I’m not really up on the contemporary criticism in this field. It’s really a battlefield, filled with academics like Roman legions on the plain, who question the very integrity of a text and also seem to imply that you’re not reading what you think you’re reading. But I will go on as if that weren’t happening.

For those of you who are at the beginning of a writing career, it might be a good idea to put off the reading of Grub Street for a little while. The tortured author in this novel has the paralysis that all writers know—he can’t write at the moment—and one of his problems is the three- volume novel in demand at the time. We’ve gotten over that debilitating infection, but I don’t think there will ever be a cure for the pain expressed in the book by the writer’s wife, who is facing starvation. (That might still happen now.) One of her questions during the day is this, “What is to prevent your writing, dear?” What is to prevent it? Well, that’s a sort of homicidal question, I think, the kind of domestic question that’s most dangerous – when you keep being asked by a friend just the horrible question you’re asking yourself.

It’s a curious thing to get up in the morning and write a little something. It really is a very odd occupation, I think, and the tools of the trade, the pencil, or pen, or typewriter, or word processor, these are instruments that work on behalf of the writer’s imagination. It looks a lot like secretarial work and perhaps some of it is. Someplace years ago, I read that Paul Valéry said that he couldn’t bear to write a novel (though he did write one, a very peculiar one, of course) because he thought it was utterly degrading to sit down and write, “Madam put on her hat and went out the door.”

When the author is composing, the most important reader is himself. This reader, like every other reader, is a critic. Still, there’s an eventual reader, not the writer himself, who comes into this murky process of writing. There is always the question of just to whom a certain piece of writing is addressed. To address someone smarter or even as smart as you are has its dangers, of course—you court rejection. Yet I think it is an honorable act that can incline the writer to do the best work possible. Writing, this loathsome, sedentary work, is, of course, violently active.

Reading is thought to be passive, and by comparison to writing, I guess that’s true enough. On the other hand, to overwhelm a book, to engage it, to throw it to the ground without injuring yourself, you need all the practice and skill, say, of a student of the martial arts.

Perhaps there is some inborn talent involved in appreciating imaginative literature, something called the reader’s imagination. Some critics have maintained that the words on a page in a novel or story are really cutlines, sketches that promote the imagination of the reader to create in his own mind the characters and to participate in this moving pageantry of action, human reality and emotion brought about by a sentence such as, “Mary tossed her head and Henry groaned because he knew what was coming.” That sentence is very different, of course, from another sentence, a very short one, which is, “Call me Ishmael.” (At the time of Melville, of course, the son of Abraham and Hagar had a kind of resonance for the public, and perhaps it doesn’t in our time.)

Anyway, when you think about reading, you begin to think about time, that profound reality and abstraction. Our life shows a determination to provide methods of time-saving: in the kitchen, office, and so on. But this saving does not seem to accumulate. I don’t know where it is, the time that’s been saved! People with time on their hands are an object of pity. Old, retired people are constantly told to keep busy. But you can’t read if you’re always busy! In fact, to read you have to sit around all day doing nothing. During the presidential primaries, the candidates were asked about their reading and I don’t remember the actual books they managed to excavate (that’s what it felt like) from the recesses of their heads. I do remember that the books were either for relaxation, as they rather proudly said, or for quick information. One of the results of genuine power in business, politics, law, medicine, is that there is no time to read imaginative works. For those who actually run the country, summary is a passageway to wisdom about the most complex matters of moral and practical life. In a sense, the contents of the political and corporate mind, I think, would be grossly disturbed by contemplation of the wisdom of the ages, since such wisdom tends to undermine self-importance. By not reading, they’re quite happily cut off from a lot of downright insults.

Tonight we’re here in this beautiful Morgan Library. The aura of a public library has somewhat declined as a live, national institution. For myself I like to remember those reading and studying generations in the New York Public Library, which was filled with scruffy intellectuals— contentious, learned people. Some of these people actually used to say, “My university is the New York Public Library.” This is especially true of immigrants and children of immigrants. Louis MacNeice has a beautiful poem about the reading room of the British Museum and it has these lines in it, “ Beneath enormous fluted Ionic columns/ There seeps from heavily jowled or hawk-like foreign faces/ The guttural sorrow of the refugees.” I was in the elevator of the library one day during World War II, a time when the most malnourished, unhandy, awkward sort of bookish young men were being called into the army, and I heard one girl speaking to another: “How does Jack, or Sam, whoever, like it at Fort Dix or Fort Bragg?” And the answer was: “He hates it: they’re all Neo-Platonists there.” Well, there was the New York Public Library of the old days.

All those who write have to deal with a steady increase of ennui on the part of the reading public. The question so hostile to the arts today is, “So, what’s new?” This boredom would seem to put the reader in ascendency over the writer, and that’s an ascendency the reader has not earned.

Well, even Madame Bovary had occasion to remark that she was beginning to find an adultery in the boredom of marriage.

Anyway, to consume a book is not like consuming clothes, furniture, jewelry, caviar, and so on. And there is a difference between books as commodity and as literature, between the wish to write a book, which every citizen has, and the wish to make a contribution, however small, to literature. An experienced reader knows without being able to define it when the author has paid a certain kind of attention to his task that will ask a great deal of the reader. A challenging work of the imagination asks the reader in a sense to pay, like putting tokens in the subway, for the pains, inspiration, and daring of the author. To do his part in this community of two, writer and reader.

Dr. Johnson said, “People in general do not willingly read if they can have anything else to amuse them.” Perhaps a passion for reading is an idiosyncrasy. I suppose there is not much we can do about that, and it’s not good to have too much vanity about any of our cultural virtues. Proust left a short book which he called On Reading, and with his rich eclecticism he had things to say about William Morris, Carlyle, Ruskin, the Dutch painters, along with reflections on Racine and Saint-Simon. But, in the end, he notes the insufficiency of reading. He says it is initiation and not to be made into a discipline. He ends the book with this sentence: “Reading is at the threshold of spiritual life. It can introduce us to it. It does not constitute it.” I don’t want to end on that beautiful and mysterious sentence, but on the contract between the reader and the writer. The salutation “Dear Reader” comes from a more intimate age, and to use it now is an affectation and not likely to be particularly amusing. But nevertheless, there is a dear reader for whom the terrible pains taken by the writer are actually sacred.

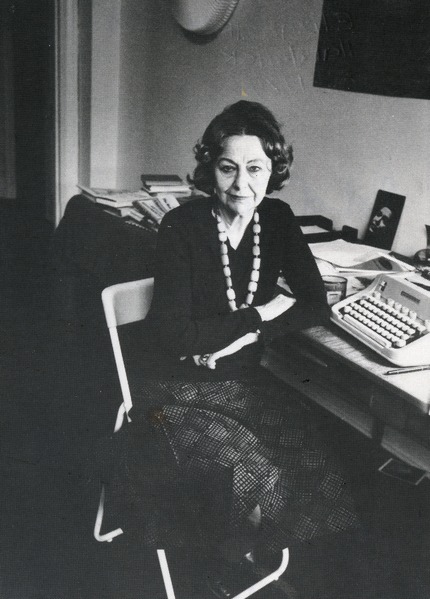

Elizabeth Hardwick (1916-2007) was born in Lexington, Kentucky, and educated at the University of Kentucky and Columbia University. A recipient of a Gold Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she is the author of three novels, a biography of Herman Melville, and four collections of essays. She was a co-founder and advisory editor of The New York Review of Books and contributed more than one hundred reviews, articles, reflections, and letters to the magazine.

Copyright 1989 © The Elizabeth Hardwick Estate, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC