Thank you very much. The signs of literary talent may appear early or later. John Aubrey, for example, the 17th century gossip, whom we have to thank for the rumor that Sir William Davenant was an illegitimate child of William Shakespeare's. Aubrey also reports that the dramatist Shakespeare showed a definite gift for theatre when he was very young.

According to Aubrey, Shakespeare's father was a butcher, and when Shakespeare was a boy he was wont to exercise his father's trade. And, says Aubrey, when he would kill a calf he would do it in high style, and make a speech. What these speeches are, neither history nor gossip records, but I think everybody recognizes that the story has a kind of mythic truth to it.

Somewhere within all of us there exists that little show-stealer whose first performances are by the royal command of the homunculus self, you might say. Each of us is bound to have some memory of him or her [throwing] all kinds of creative, fantastic shapes in the course of our childhood, and indeed, adolescence.

We might, with a nod to the young Shakespeare, call it a stage, as it were, a stage we all go through, perhaps the eighth of man, or woman. I certainly can remember being elevated above my usual self on the few unforgettable occasions when I climbed the galvanized roof of the henhouse in our farmyard in County Derry, and saw the road from a higher vantage point altogether.

It was almost a God's-eye view, and it awoke the appetite for walking on air, an art which has become one of my favorite analogies for the art of literary composition. Those who walk on air, of course, live in perpetual fear of putting their foot in it, you might say.

One false linguistic move and the air bridge - which is how Czesław Miłosz describes one figure of what a poem is, a bridge made of air, over the air - one false move and the air bridge collapses under you. You might extend the figure by connecting it with another simile used by Polish poet Julia Hartwig, who spoke of her need to feel the sentence under her feet like the solid earth.

Hartwig's desire, obviously, is one experienced by every writer, the desire to feel what is written, be it the sentence or the verse line or the stanza or the whole finished thing, to feel that under his or her feet like it was made of perfectly-pitched sounding boards.

Every writer, in other words, wants to live in the house that art built, and wants to know further that the house and its contents are comprehensively insured. But between that desire and the reality there usually falls some shadow of self-doubt.

Not everybody possesses the kind of confidence that William Blake had, who provided us with a kind of self-portrait, I think, of the kind of writer he was when he wrote with accelerating cogency, "If the sun and moon should doubt, they'd immediately go out."

Even Emily Dickenson was anxious for approbation, as was Sylvia Plath. Even W.H. Auden did, whom I always thought of as a kind of self-born oracle, a kind of one-man language shift, a kind of jackpot [pulled] out by English in one of its better moments.

Even Auden has revealed in his recently-published "Juvenilia" to have gone through periods, the usual periods of artistic fantasy, like early on when he thought he was somebody else: at various stages Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas, indeed, A.E. Housman.

So, one of the first things to be said about the Whiting Awards is that they are a wonderful antidote to self-doubt as a writer. The great thing about these prizes is, first and foremost, the boost they give a writer by supplying that worthwhile bundle that Bob spoke of.

I know that the recipients are characterized, and indeed do, in their appearance, give all evidence of this, as being young, or younger, writers. I also know that the bounty they have received will augment not only their confidence, but their finances, and to some extent, their freedom.

But I can assure them from some experience as a not-so-young writer, that the unexpected arrival of a horde of doubloons and pieces of eight into your life at any stage has a definite salubrious affect. So I can only wish for each and every one of them that they will go on being afflicted by what you might call the Danae effect. Danae, remember, was the one into whose lap the god Zeus arrived as a shower of gold.

What every writer dreams of, I suppose, is a kind of copious downpour like that arriving regularly from on high, no strings attached, with no consequences except the issue of a work as radiant as the gold which sponsored it. But I, myself, grow aureate. So let's put it real plainly.

It has to be said that patrons in all stages of the history of literature have been important. The farmer poet, Hesiod, in ancient Greece may have been able to support himself on his own land on the slopes of Mount Helicon, with the aid of the muses, of course. But from ancient Greece through Anglo-Saxon England, right up until 19th-century Ireland, the bard supported by the lord or the itinerant minstrel, supported by his listeners, this has been a constant feature of the literary landscape.

Nowadays, of course, it is the poetry-reading circuit which keeps the wolf from many a poetic door. And I, it has to be said, and innumerable other Irish poets, and other guests in your nation, as well as poets and prose writers who were born here and belong here, all of us have had occasion to be grateful for the sponsorship afforded by universities, by foundations, and by institutes of various sorts within the United States.

A great number of these bodies are like the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation, the result not only of generous impulse on the part of private individuals, but of clear forethought and a founded belief in the value and reality of artwork as itself, per se.

Such sponsorship and such patronage have made the difference in many lives, not least in the life of the aforementioned W.H. Auden, who once wrote a very attractive, scampish poem called "On the Circuit," to tender his thanks in his own inimitable way to those who hand out the checks, and also those who attend, of course.

At the end of his poem, "On the Circuit," the line goes, "Another morning comes: I see, Dwindling below me on the plane, The roofs of one more audience I shall not see again. God bless the lot of them, although I don’t remember which was which: God bless the U.S.A., so large, So friendly, and so rich.”

I have to say that my own gratitude to patrons and benefactors began early in another country 30 years ago this year, when my first book won the Somerset Maugham Award. I'm glad to see that most of the people here have been affected by the Danae syndrome already. So I hope it keeps sticking to them, as it were.

But this Somerset Maugham Award was endowed by Maugham's [will], and it's still given to young writers to allow them a chance to live, or at least travel abroad for a short period. In 1969 it provided enough for my wife and myself and our two small boys to go away and spend the summer in a farmhouse in the Bas-Pyrenees region of France, inland from Bayonne, among the maize fields, along those olive-green willow-wafted rivers. They call it Le Gave.

It meant that for a significant number of weeks daddy, who was usually a university teacher and, [however], a party-goer, could get up each morning, go to his desk, and write, rather than go to the college to teach. But you're isolated from the usual circumstances and the usual responsibilities and the usual distractions, and indeed, those weeks were very important to me, personally.

It gave you a chance to test out what it would be like to live the vocation not as a part-time person doing it at night, as it were, but to go fulltime, what it was like to test yourself for a more full commitment. Now, I wasn't quite the kind of expatriate scribbler that Maugham himself was, the kind whom poet Phillip Larkin would later characterize as the shit in the chateau.

Larkin was a stern believer in working for a living and then doing it later on when he went home for pleasure. He said that poetry to him was like knitting, as far as I recollect. Anyway, if I wasn't that kind of chateau dweller, I was nevertheless, as I say, giving myself a trial run.

So in 1972 I resigned my teaching job at Queens University, Belfast, and went to live with that gallant wife and two children in a small gate lodge in County Wicklow, 25 miles south of Dublin. Forgive me this little personal anecdote, but it's about what can flow from encouragement, patronage, and support systems for writers at a crucial stage, which I would put anywhere from 24 to 94.

Anyway, our children were just starting school at this time, and on the first morning when I took them down to the local public school—we had moved from Belfast way down to Wicklow—I took them down, and I had this wonderful moment of confirmation. The principal of the school was taking down the particulars of their names and ages, dates of birth and so on.

And then he had to fill in one column in the role book which was reserved for the parent or guardian's occupation, and this he did without any hesitation and without any inquiry from me. Since this was a country district, of course the grapevine had been at work. Everybody knew exactly what had happened.

So he entered in that column for parent's occupation, he entered it in the Irish language, because Irish was, still is the official language of the schools there, he entered the word 'file.' Now, if you'd asked me I would have probably said something like scríbhneoir, scribe, scribbler, scríbhneoir, meaning writer.

But he wrote the absolute word 'file,' which means poet. Now, it was a big thrill. I've never said it myself. But somehow the encouragement afforded by the Somerset Maugham Award had been influential in leading to that denomination at that moment.

So things had changed then, and they have changed more and more, I think, through these benefactions, changed certainly from the years last traveling, rambling, Irish 'file', the poet Anthony Raftery.

Rafter was rambling in the west of Ireland 100 years ago. Well, sorry, he died about probably the 1860s. He was a blind fiddler and poet, and he left one of the best-known poems about being in need of patronage. This is a poem that every schoolchild used to know in Ireland. I say it Irish. I'll say it in English.

"Mise Raifteirí, an file, lán dóchais is grá le súile gan solas, ciúineas gan crá Dul siar ar m'aistear, le solas mo chroí Fann agus tuirseach, go deireadh mo shlí Feach anois mé m'aghaidh le bhalla, Ag seinm ceoil do phocaí folamh."

"I am Raftery the poet, full of hope and love, my eyes without eyesight, my spirit untroubled. Tramping west by the light of my heart, Worn down, worn out, to the end of the road. Take a look at me now, my back to a wall, Playing the music to empty pockets."

But important as awards have been to all us of us, what is probably more important is the encouragement of other artists, older, respected people in the mystery. In my own case at that moment of transition from teacher to fulltime risker, two people were very important.

One was a painter called Barrie Cooke, who lived in Kilkenny, who had never had a job, as it were, and the other—and I had written his name before today—the other was poet, Ted Hughes, who, alas, died yesterday in England. It is a cause of great personal sorrow to me. He died suddenly.

But it should be said that not only did he encourage me by believing in the work and being a support, but that continued, and that is one of the great graces in any writer's life, to have a respected person who is completely trustworthy that you can tell the whole truth to about the other writers.

Everybody needs at least one of those. This is not in the script but it seems proper to say one word in memory of Ted at this moment.

There is a beautiful poem, 15th century bardic poem, by an Irish poet called Tadg Óg Ó hÚigínn, and it's in memory of his elder brother who was an Archpoet who taught school of poetry. This is a lament for the death of his elder brother who was a master poet. I'll just read two or three lines. I translated it myself.

I don't remember the Irish, but this is a translation towards the end. He's speaking of the death of the poet.

"By his death I realize how I value poetry. Oh, [heart] of our mystery, empty, and isolated always. [Aine's] son is dead. Poetry is daunted. A stave of the barrel is smashed, and the wall of learning broken."

As I say, the knowledge that one was believed in by someone like that was crucial, and I think that is the second great thing to be said here this evening about the Whiting Awards. The recipients are nominated by other writers. They come here in the knowledge that it is other workers in their art who have commended them.

This is surely the main reason why this evening's winners can rejoice unabashedly in their good fortune. No commendation quite substitutes for the commendation of the respected practitioner. That laying on of the hands marks the soul for the better, and marks the memory forever, I think.

I shall always remember, for example, a sense of blessing I myself experienced a couple of years after we had gone to that cottage in Wicklow, when Robert Lowell visited the cottage in 1975. He wasn't used to cramped circumstances. He was in that time living in a big house called Milgate in the south of England with Lady Caroline Blackwood.

It was a spacious, large country house. He came into this little cottage. He expressed his sense of the space very subtly, as Lowell did always. He said, "You see a lot of your children here."

Anyway, he had seen my work. He still came to the house. These things mean something. You don't really have to talk about poetry or talk about work between you to get some sense of confirmation. Anyway, when Lowell was leaving he said, "I'll pray for you," and this even after our eldest boy, [Michael], had told him with the candor of a nine-year-old, "I know you're a famous poet, Mr. Lowell, but it's my ambition to meet a famous footballer."

I want to thank the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation for giving me the opportunity to share in this occasion, to say again, on behalf of the winners, and all our behalves. Admirable, the work is that they continue to do, and the disbursements they continue to make, and especially because they canvass the wider writing community, and especially, too, because the recipients are now in a line of succession with people who have distinguished the awards by receiving them in the past.

We wish each and every one of this evening's recipients even an ever more solid footing in the language and in their own pursuit of their art, not, as Czesław Miłosz writes, "Not to enchant anybody, not to earn a lasting name in posterity, but an unknown need for order, for rhythm, for form, which three words are opposed to chaos and nothingness." Thank you very much.

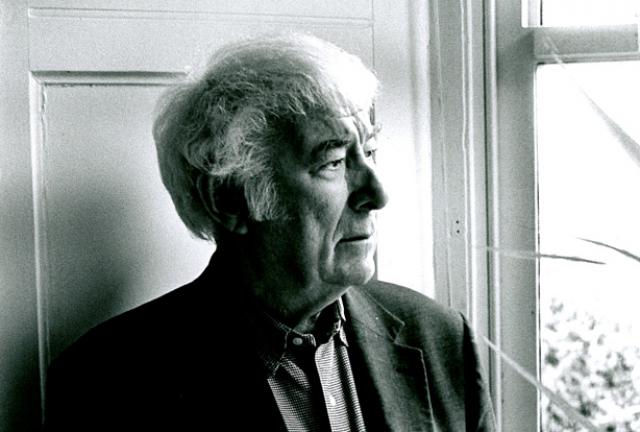

Seamus Heaney was born in 1939 in Co Derry, Northern Ireland. The eldest of nine children, he was educated at St Columb’s College, Derry, and Queen’s University Belfast.

His first book, Death of a Naturalist, was published by Faber and Faber in 1966, the first of eleven volumes of poetry – as well as criticism, plays and translations – which would establish him as one of the leading voices of his generation. He was the recipient of numerous prizes and honours, including the Whitbread Book of the Year in 1996 and 1999. In 1995, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, for ‘works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth’. He died in 2013.

(c) Estate of Seamus Heaney