Thank you very much, Robert. I have to admit, I'm a sucker for awards programs. I always watch the Academy Awards, the Golden Globe Awards, the Kennedy Center Performing Arts Awards, and more. I think I have drawn the line on the Country Western Awards.

Anyhow, you can imagine how pleased I am to be asked to be part of the Whiting Awards Program this evening. I feel like a puppy with two tails. One of my favorite scenes in all of literature occurs in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, after the dodo has staged the caucus race. If you'll recall, it required all participants to run around in circles and get nowhere.

I suggest this was Lewis Carroll's vision of political committees, hence the word “caucus.” In any event, at the conclusion of the so-called race, everyone wants to know who has won, to which the dodo announces, "Everybody has won, and all must have prizes." That, to me, is a wonderful concept, but alas, it rarely happens in real life.

So I'm always thrilled to see someone actually win a prize, like those of you selected to be honored this evening. Before I moved to Houston a decade ago, I attended this ceremony each October. I also recall the Academy Awards ceremony for 1968. Ruth Gordon, a septuagenarian at the time, received the Oscar for best supporting actress for Rosemary's Baby.

Ms. Gordon rushed up to the stage and announced, "You don't know how encouraging a thing like this can be to a girl like me." The remark brought down the house. But surely this is the point of awards: encouragement as well as recognition, especially encouragement for young achievers such as yourselves. But as Ms. Gordon's remark testifies, we all need encouragement at all stages of our lives.

Remember another Academy Award winner, Sally Field, when she was stunned at the applause? "You like me! You really like me!" she said. Just where is this encouragement to come from? While there are a few, there are not many foundations willing to recognize artists at any stage. This is where the Whiting Foundation has performed an unequaled and extremely generous function.

We have come, alas, to expect not much from the federal government. As the poet Donald Hall has observed, when the naysayers in Congress and the fundamentalists who want to kill off the National Endowment for the Arts speak of the American Dream, what they mean is America's prospects for comfort and prosperity, not America's prospects for beauty, mind, spirit, inspiration, or pleasure.

Speaking of the National Endowment for the Arts, Mr. Hall did some homework. Do you know what it costs every taxpayer annually? Forty cents. That's right, forty cents, and for that we would close down the regional theaters, silence opera houses, and bare the walls at museums and galleries. It's no wonder the American artist often feels as if he or she is working in isolation, and I would suggest especially the writer.

Painters, musicians, dancers, and actors, are all encouraged to study all along their careers. Singers and actors continue to work with voice and dramatics coaches, or to attend master classes. There is no master class in America for the writer.

Oh, sure, there are writers' workshops, thousands of them, but after a certain point in a writer's careers workshops are no longer useful. Part of it is the democracy of a workshop. Why hear your work criticized by writers less experienced and probably less good than yourself? As Ezra Pound observed, there is no democracy in the arts.

A lot of students get into workshops who have no business being there. In one famous encounter someone asked Flannery O'Connor, "Ms. O'Connor, do you think writing workshops discourage writing students?" to which she replied, "Not enough of 'em."

On the other hand, it is a myth that writers work entirely alone. They do, at their desk and their computers, but if they work entirely alone, then why are there so many dedications and acknowledgements to spouses, lovers, best friends, agents, and editors who reviewed their drafts and manuscripts?

Historically, writers have enjoyed a close, critical community. Shakespeare gave his friend Ben Jonson a helping hand by getting the Globe Theatre to produce Jonson's Every Man in His Humor, his first theatrical success. Shakespeare even went so far as to join the cast himself.

Walt Whitman sent Emerson a first edition of Leaves of Grass. Emerson was the most widely-respected person of letters in America at the time, and the one best qualified to understand Whitman's unique achievement. Emerson wrote back a letter of heartfelt appreciation, which concluded with the words, "I greet you at the beginning of a brilliant career."

He also called the book, "The most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed." Only 300 or 400 copies of that first edition were sold. Take heart, young writers. But using Emerson's letter as a blurb, Whitman issued an enlarged second edition, and the following year a third edition. I am sorry to say that he also published Emerson's letter in The New York Tribune without Emerson's permission. But as Truman Capote once said, "A boy's got to hustle his book."

Another example of literary generosity was when Robert Frost's first book was published. He was approaching the age of 40, and the book was not taken in America, but in England. It was favorably reviewed by the British poet Edward Thomas. In discouragement, Frost had moved his family to England, and he had met Thomas and they became friends.

When Frost's North of Boston was published, Thomas reviewed it and declared Frost's poems to be masterpieces. When Frost returned to America, he found that almost a miracle had occurred. When he had left he had been virtually unknown. When he returned he found the literary world eager to welcome and to honor him.

For a book a poetry, North of Boston became a bestseller. Frost was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, he accepted an invitation to join the faculty of Amherst College, and this was all largely due to his reception in England, and especially the one review and praise of Edward Thomas.

Young Hemingway learned style from Gertrude Stein. "Gertrude was always right," he said. In gratitude, Hemmingway persuaded Ford Madox Ford to serialize her book, The Making of Americans, in Ford's Transatlantic Review.

I could regale you with many stories of literary friendships that have helped launch careers. When Shelley met Byron, the latter was famous. His "Childe Harold" had made Byron's fame overnight. Shelley's first long poem, "Queen Mab," had been reviled by the critics, and made him no reputation at all except disgrace. Byron gave Shelley confidence, if nothing else.

Their friendship is recounted in Louis Auchincloss's fine book, Love Without Wings: Some Friendships in Literature and Politics. It also examines the relationships between Rimbaud and Verlaine. Rimbaud was an unknown before he met Verlaine, who praised the young man's language, his achievement, and this style.

It often is assumed that an older writer will befriend and aid the career of a younger, but it can, and perhaps should, go the other way as well. I'll give just one example from my own experience. In the early 1980s my friend, the fiction writer Elizabeth Spencer, was stuck on a novel and discouraged.

I suggested that she collect her short stories. There had only been one volume of them so far, and I knew she had many. She balked, saying what she needed to do was to publish another novel, and that was that. Besides, no one could possibly be interested in publishing her short stories.

I persisted, the old water on limestone method. Finally Elizabeth produced the 430-page volume called The Stories of Elizabeth Spencer. It was enthusiastically accepted by Doubleday, who published it with a glowing forward by Eudora Welty. It was reviewed on the front page of The New York Time Book Review. For it Ms. Spencer received the Merit Medal for the Short Story from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, to which body she was elected two years later. All of this, or some of this, might not have happened if a much younger writer had not given an older a necessary push.

Henry James once wrote, "Be generous and delicate, and pursue the prize." By all means, pursue the prize for yourself, but along the way be generous to others, particularly to other writers. There is enough glory for all of us to share. I have never understood the mentality of the American novelist Gore Vidal, who once proclaimed in print, "It's not enough that I succeed. My friends must fail badly."

The late poet James Merrill is an example of an artist who gave very generously. He could have lived the life of a playboy. He was the son of the founder of Merrill Lynch, and did not have to work, though few people have worked harder. In his abbreviated lifetime he produced 16 books of lyric poetry, including the epic narrative, "The Changing Light at Sandover," two novels, several plays, a book of essays, and a book-length memoir.

With his personal wealth he established the Ingram Merrill Foundation. Ingram was his middle name. Even here he was exercising his modesty, not going public. And he bestowed grants to writers he found promising. One could not apply for these grants. He also gave grants to institutions which interested him.

When I was director of the poetry reading series at the Katonah library, which Mr. Pennoyer was kind enough to mention, I invited Merrill to give a reading. He accepted, and gave me the names of several friends in the area he would like to have invited.

He had a marvelous Sunday afternoon, he said, and apparently this was so, because several weeks after his reading the librarian received a letter from the Merrill Foundation saying they would like to fund a project for the library. Was there anything the library could use?

Well, this letter created more excitement in the library than a fox invading a chicken coop. The librarians huddled, and finally wrote back that they'd never been able to afford The New York Times on microfilm. Did the foundation think this might be fundable? The response came shortly in the form of the entire run of The New York Times on microfilm, plus the machine on which to view it. Bless you, Jimmy Merrill.

When Patrick White received the Nobel Prize in 1973, he donated all the money to create a continuing award for Australian writers. Now, not many of us have that kind of wherewithal at our disposal over a lifetime, or even once, but there are other ways to be generous.

I know of several writers who, when they've had good years due to a bestseller or a Guggenheim or whatever, endorse their reading fees back to the sponsoring organization to be used for fellowships for students. William Starr engaged studio space on his property to James Baldwin. Daniel Stern gave lodging to Bernard Malamud when he was writing the stories in The Magic Barrel. Generosity does not have to be monetary.

A close friend of mine who's a very famous writer, indeed, and a winner of the National Book Award in Fiction, continues to volunteer to judge literary contests. Sometimes hundreds of book-length manuscripts arrive at her doorstep at once. I once asked her, "Joyce Carol, why do you continue to read all these contest manuscripts?" And she replied simply, "If I don't do it, someone less responsible might."

So let me congratulate all the winners tonight. It's heartening to see intelligence and creativity rewarded in the place of brute force. One piece of advice: never listen to critics. I mean professional critics, not your friends that you share your work with. They can help a lot. But no one ever built a monument to critics. They have, and will, build monuments to poets and good creative writers.

I wish to make a charge to you tonight. I charge you with the responsibility through your life and work and example of trying to help bring about a change. We read in the newspapers that our nation's test scores are falling behind other nations in science, languages, and general knowledge. With a heavy heart I read that according to an NBC news poll conducted last year, the best-known Americans are Richard M. Nixon, Billy Graham, and Mr. Whipple.

If you don't know who Mr. Whipple is, I congratulate you. He's the grocer on commercials on TV who admonishes the housewives not to squeeze the Charmin toilet tissues. It is perhaps not so much the fault of the public as it is the media that literary and awareness are in such a state.

As proof of my feeling I will share with you a little poem, a [near] villanelle that I composed from actual newspaper headlines that I'd gathered over a few years. I haven't changed a word of the headlines.

"Headlines"

War Dims Hope for Peace.

Plane Too Close to Ground, Crash Probe Told.

Clinton Wins Budget; More Lies Ahead.

Miners Refuse to Work after Death.

Include Your Children When Baking Cookies.

War Dims Hope for Peace.

Something Went Wrong in Jet Crash, Experts Say

Prostitutes Appeal to Pope.

Clinton Wins Budget; More Lies Ahead.

Local High School Dropouts Cut in Half.

Couple Slain; Police Suspect Homicide.

War Dims Hope for Peace.

Stolen Painting Found by Tree.

Panda Mating Fails; Veterinarian Takes Over.

Clinton Wins Budget; More Lies Ahead.

Iraqi Head Seeks Arms.

Police Campaign to Run Down Jaywalkers.

War Dims Hope for Peace.

Clinton Wins Budget; More Lies Ahead

Now some individuals actually wrote these, and someone approved them, and they were proofread.

W.H. Auden said of artists, "We were put on earth to make things," and I might add, “To make things better." We can do so by being generous as well as by being creative, by becoming a master class to someone else. We all have it within us, the capacity to make someone else's luck.

It was Chesterfield who reminded us that the artistic temperament is a disease found only in amateurs. I would hope you would follow the example of the professor who narrates the wonderful poem by Galway Kinnell, “The Correspondence School Teacher Says Goodbye to His Poetry Students.” Many of you, I know, know the poem.

Goodbye, lady in Bangor, who sent me

snapshots of yourself, after definitely hinting

you were beautiful; goodbye,

Miami Beach urologist, who enclosed plain

brown envelopes for the return of your very

“Clinical Sonnets”; goodbye, manufacturer

of brassieres on the Coast, whose eclogues

give the fullest treatment in literature yet

to the sagging breast motif; goodbye, you in San Quentin,

who wrote, “Being German my hero is Hitler,”

instead of “Sincerely yours,” at the end of long,

neat-scripted letters extolling the Pre-Raphaelites:

I swear to you, it was just my way

of cheering myself up, as I licked

the stamped, self-addressed envelopes,

the game I had of trying to guess

which one of you, this time,

had poisoned his glue. I did care.

I did read each poem entire.

I did say what I thought was the truth

in the mildest words I knew. And now,

in this poem, or chopped prose, not any better,

I realize, than those troubled lines

I kept sending back to you,

I have to say I am relieved it is over:

at the end I could feel only pity

for that urge toward more life

your poems kept smothering words, the smell

of which, days later, would tingle in your nostrils

as new, God-given impulses

to write.

Goodbye,

you who are, for me, the postmarks again

of shattered towns—Xenia, Burnt Cabins, Hornell—

their loneliness given away in poems, only their solitude kept.

The operative words of that poem, I think, were "I did care, and in the mildest words I know." To our honorees this evening, I hope your lives are crowded with more honors, but I hope you will dedicate some portion of your energies toward helping your fellow artists, and to service to improve the general good and the general literacy of our nation.

I'm reminded of the acceptance speech made by Peter Taylor when he received the Gold Medal for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1979. Mr. Taylor said, "The fact is that I've always had a wide circle of highly intelligent, greatly gifted literary friends whom I respected and whose respect I've enjoyed, and that has been the kind of glory I have had. I have somehow found my glory and my satisfaction in that circle of glories."

May each of you here tonight know such glory. Thank you.

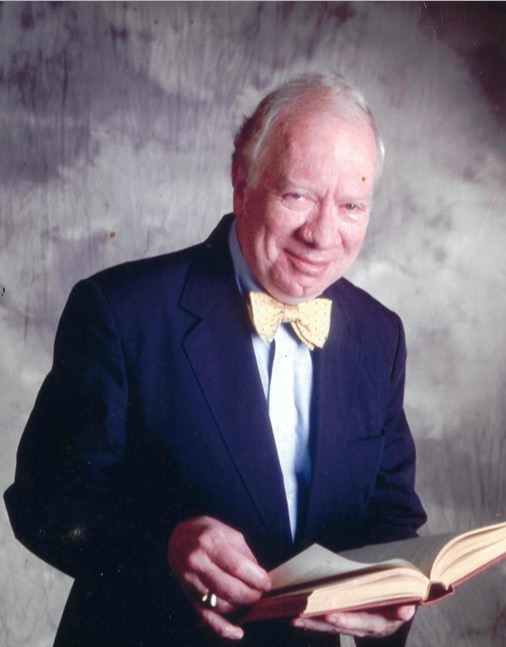

Robert Phillips has had two careers: One as copywriter and advertising creative director, and the other as a teacher of creative writing. He was Director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston. He has published 30 books of poetry, fiction, and essays.