-

The Sorrows of Others: StoriesFrom"Silence"

Prancing down the building’s stairs, Hui concentrated again on the boy who had stopped returning her calls. Acknowledging another’s pain obscured one’s own. Hui wasn’t ready yet to accept that. From the window, Meng watched her granddaughter walk up the tree-lined street. The old woman’s longing was like that of a child, featuring prominently in her eyes, which captured that spirit from her youth. It would have been easy for anyone to picture what she had looked like back then, if anyone had been there.

The Sorrows of Others : Stories

The Sorrows of Others : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

The Sorrows of Others: StoriesFrom"Julia"

When they asked what she would miss most about New York, she said the ubiquity of art, how it could be found on the streets and in museums, in the people and the ways they chose to live. She knew this was the answer they were seeking, the one that assuaged the precarious matter of continuing in New York, which was brought into question every time another person chose to leave. Art was what she loved about the city, what everyone loved, but it wasn’t what she would miss. She would miss the drugstores that punctuated every block, some of them converted from beautiful old buildings, giving them that stumbleupon quality she’d have to do without in a place like Nashville, where people drove cars and drugstores were treated more respectfully as destinations. After work, or before a night ended, the rows of products provided a sense of order, filled with latent possibility. The colors—condoms, toothpaste, Zyrtec, folic acid—were brighter, more abrasive under white overhead lights. She loved going in and discovering a need she hadn’t known was there. It felt good going home not empty-handed.

The Sorrows of Others : Stories

The Sorrows of Others : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

The Sorrows of Others: StoriesFrom"Any Good Wife"

In August, shortly after the start of the fall term, he came home to a dome on the table, the color and translucence of urine. Lettuce and small tomatoes make a wreath around the perimeter. Inside the dome, sliced radishes and shredded cabbage were suspended in space.”The food is trapped?” he’d asked, wondering if this was a joke or a game. “How do I get to it?” “You eat the whole thing,” Ailian said, looking pleased with herself. “It’s lemon-flavored. They call it Jell-O.”

The Sorrows of Others : Stories

The Sorrows of Others : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

Category 2

-

Unaccompanied: PoemsFrom"Cassette Tape"

Mamá, you left me. Papá, you left me.

Abuelos, I left you. Tías, I left you.

Cousins, I’m here. Cousins, I left you.

Tías, welcome. Abuelos, we’ll be back soon.

Mamá, let’s return. Papá ¿por qué?

Mamá, marry for papers. Papá, marry for papers.

Tías, abuelos, cousins, be careful.

I won’t marry for papers.

I might marry for papers.I won’t be back soon. I can’t vote anywhere,

I will etch visas on toilet paper and throw them from a lighthouse.

Unaccompanied: Poems

Unaccompanied: Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Solito: A Memoir

People dust themselves. One by one, we stand. I dust myself. Look at the pinholes in the sky’s dark blanket. Stars twinkling. ¿Why do they blink like that? ¿Can they see the dirt under our feet? Like old newspapers. Crinkle. Crunch. Like walking on eggshells. Crack. The gallons of water in people’s hands. Slosh. We’re walking again.

Mice or bunnies sometimes cross our paths. Bats overhead. If I see them, I say they’re my pets. I do the same with the strangers: we’re all a family. Dad in front of me. Mom and Sister in front of him. The Six are my immediate family. I have so many faceless cousins, uncles, and aunts. Uncle #22 drifts off to the side to take a piss in the bushes. Aunt #6 steps to the side to take a sip of water. We push forward like a snake.

Solito : A Memoir

Solito : A Memoir- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Unaccompanied: PoemsFrom"Second Attempt Crossing"

In the middle of that desert that didn’t look like sand

and sand only,

in the middle of those acacias, whiptails, and coyotes, someone yelled

“¡La Migra!” and everyone ran.

In that dried creek where forty of us slept, we turned to each other,

and you flew from my side in the dirt.

Black-throated sparrows and dawn

hitting the tops of mesquites.

Against the herd of legs,

you sprinted back toward me,

I jumped on your shoulders,

and we ran from the white trucks, then their guns.

I said, “freeze, Chino, ¡pará por favor!”

So I wouldn’t touch their legs that kicked you,

you pushed me under your chest,

and I’ve never thanked you.

Unaccompanied: Poems

Unaccompanied: Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Trace Evidence: poemsFrom"Exile"

It happened inside a single room.

For me. Forgive me

If you feel with this assertion I diminish you

Or the integrity of your story.

But it’s true: I was nowhere, there,

On the frayed brown carpet, between two beds—

Mine to the right, my brother’s to the left—

Counting the tiny holes

In the radiator cover, dark eyes

Piercing through painted-white metal.

When I looked around, I saw nothing that I was.

Not even other nothings, like me.

Do you think I take from you?

I do not take from you, I am you.

Trace Evidence : poems

Trace Evidence : poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Trace Evidence: poemsFrom"Thirty-Seventh Year"

At the start of this narrative, I will pretend

Not to be alive, not to be

Speaking to you from the living earth.

To help you. I will pretend

The circumstances of our being

Here, together, are casual—

And not incidental

Of this awkward dilemma: How to coexist

When you would like me dead.

For simplicity. For lack of threat.

In this narrative, I will look

At you from a distance, as into the future,

No more real than I am,

Sitting here in my off-white body which I can feel

But is somehow less important, less

Urgent than the problem it poses.

Sometimes, when I write this kind of narrative,

My mind flees and all I see above is text

At once strange, because I don’t know

How to hold it, and familiar, because I wrote it—

Send out the memo, I’m nearly done here.

How much more of this life to live? Thirty years, if I’m lucky,

I bet. If my life ends, will my brothers’ finally begin?

Who made my mother? Who killed my father who lives?

Trace Evidence : poems

Trace Evidence : poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Trace Evidence: poemsFrom"While I Wash My Face I Ask Impossible Questions of Myself and Those Who Love Me"

Specks of toothpaste fleck the mirror.

A fan spins dust in the hall.

I find this is it too vulgar to accept

So I wait for a new starting point

As though life will begin there and then.

Do you know what I mean?

Not what I’m saying, what I mean.

Is it possible my function is to hold

All the intricate, interstitial pain

And articulate clarity?

Tie a boat to my wrist, I sprout wings.

Give me a pair of shoes, I grow fins.

Once an hour I trick myself into focus:

I look into the glass as I look through it.

When the new beginning comes, what then?

Does life suddenly reset like an Atari?

Does meaning emerge

Assertively and without invitation?

The task is to live well enough with you.

But how? How do you know what you want

If you don’t tell you? If you don’t hear you?

Trace Evidence : poems

Trace Evidence : poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Call and Response: StoriesFrom"Botalaote"

Whatever group of friends I told, what always fascinated people was not the boy’s dying but this image, this juxtaposition of school and cemetery, side by side, and a hill cutting them off from the ward. It was as if they thought that, away from our parents, we kids fraternized with the dead. There would often be one person who thought that I was embellishing, that I was making up these details for the benefit of a story, to create some sort of meaning. That skeptic seemed to assume that the hill—which I now knew to be just a hillock—the school, the cemetery were symbolic of something that I had overcome, something I had escaped. But the Botalaote cemetery was separated from Motalaote Lekhutile Primary School by only a narrow dirt road, and behind them the hillock cut them off from Botalaote Ward. Those were the facts.

Call and Response : Stories

Call and Response : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Call and Response: StoriesFrom"When Mrs. Kennekae Dreamt of Snakes"

Every winter, Mrs. Botho Kennekae’s husband took time off from his driving job in the city and spent three weeks at the cattlepost, where he did whatever men did there—presumably offer the softness they withheld from everyone to their cattle, for the cattle were the great loves of their lives, so beloved the men called them wet-nosed gods, so beloved the men agreed: without cattle, a man pined and lost his sleep; still, having cattle, a man fretted and lost his sleep.

Call and Response : Stories

Call and Response : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Call and Response: StoriesFrom"Small Wonders"

As Phetso dried herself, the old woman unfolded clothes from a plastic bag.

“Your uncles in Serowe have bought you these clothes,” the old woman said with formal solemnity, “to show the end of your affliction.” Then the woman handed Phetso the clothes, one by one, saying as she did:

“Receive this, panties.

“Receive this, a bra.

“Receive this, a skirt.

“Receive this, a shirt.

“Receive this, socks.

“Receive this, shoes.”

Phetso put each item on: sky-blue cotton panties; a brown cotton bra, slightly big on her; a German-print skirt that fell below her knees; a white long-sleeved T-shirt; sky-blue socks; and a white version of her midnight-blue canvas takkies. She put them on, one after the other, like a child learning to dress for the first time.

Call and Response : Stories

Call and Response : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

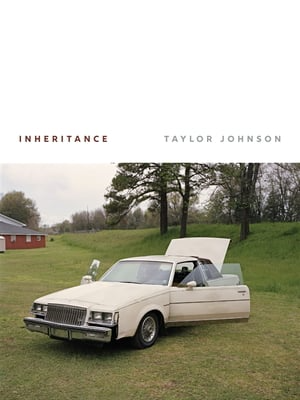

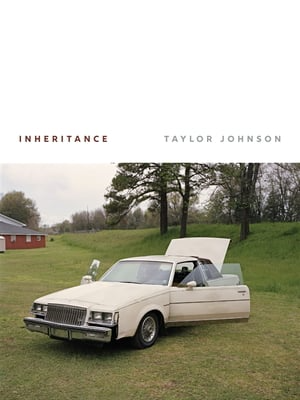

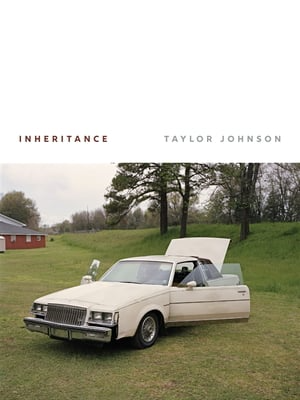

Inheritance: PoemsFrom"Conjecture on the nature of inconvenience"

If there is a ground, then there are bodies beneath it.

If the bodies know my name, then I am said to be protected.

If I am spoken for, then I could've died a number of times.

If I am still here, then I am speaking for the dirt.

If there is dirt, then there is my mouth wet and ripe with questions.

Inheritance : Poems

Inheritance : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Inheritance: PoemsFrom"The black proletarianization of the bourgeois form isn’t Kanye West’s gospel samples"

O, Death. Your singular eye. My mother speaks the King’s English. Makes quiche. Makes clove pomanders in winter. Pawned her flute. Cleaned my elementary school classroom. What is hers? Brillant song, my mother, sotto voce, in her chair asking for touch. It is drowning she means, not freedom. I swam fine. Don’t you get it, O Death, my mother is elegant alive, entering the blue hole of evening, alone. You could reach into the frame, pull her out. O Death, I’ve been crueler— I’ve watched.

Inheritance : Poems

Inheritance : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Inheritance: PoemsFrom"Trans is against nostalgia"

I’ve picked up the hammer everyday

and forgiven myself. There is a new

language I’m learning by speaking it.

I’m a blind cartographer, I know the way

fearing the distance. O New Day,

there isn’t a part of you I don’t love

to fear. I’m holding hands with

the poet speaking of light, saying I made it up

I made it up.

Inheritance : Poems

Inheritance : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

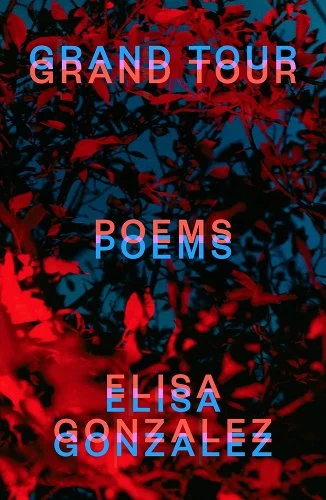

Grand Tour: PoemsFrom"After My Brother’s Death, I Reflect on the Iliad"

Alone in a London museum, I saw a watercolor of twin

flames, one black, one a gauzy red,

only to learn the title is Boats at Sea. It's like how

sometimes I forget you're gone.

But it's not like that, is it? Not at all. When in this world

similes carry us nowhere.

And now I see again the boy pelting through those galleries

a boy not you, a flash of red, red, chasing, or being chased—

Or did I invent him? Mischief companion. Brother.

Listen to me

plead for your life though even in the dream I know you're

already dead.

How do I insure my desire for grief is never satisfied? Was

Priam's ever?

I tell my friend, I want the page itself to burn.

Grand Tour : Poems

Grand Tour : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Grand Tour: PoemsFrom"The Night Before I Leave Home"

He drives too fast, as always, braking hard when he finally

arrives

at the meadow my car slid into before it slid

into an oak

where a whitetail hangs, strung

by its hind legs to drain the slit throat.

It takes more time than I expected

for death to be over,

I tell my brother. And he, a hunter, says, Yeah,

in the tone that means, Of course.

And years later I have the same voice

when he calls at 4:17 a.m. and I knock the phone off the bed,

answering almost upside-down, stretched toward him.

His pain then, I lived for it, I realize now.

Not for its existence, but to quiet with my words.

I had left so long ago. I had left.

Grand Tour : Poems

Grand Tour : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Grand Tour: PoemsFrom"Sunset"

A trampled carnation, or the red jacket sleeve

blurred on that girl quickening

after the ball

draws my mind

to the ship that I am told

is coming, preparing to anchor.

I am turned toward the sea.

It pauses at the bay’s red mouth

When everyone seems so happy, why does it delay?

Grand Tour : Poems

Grand Tour : Poems- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Snow in MidsummerA Play

DOU YI

My hands were packed in dry ice

Flown across the Pacific and

Stitched onto a man who lost his overseas.

My palms open doors to

Rooms my feet haven't walked through and

Caress a woman my eyes will never see.

It doesn't snow there but my

Nails ache when they touch ice and

Scratch strange characters onto that

Soldier's skin while he's sleeping.

His doctors call it post-traumatic stress but

He knows they're words from a

Language his tongue never learned

Justice.

Justice.

Justice

Across the East Sea a yam farmer

Uses my corneas to see.

She dreams of snow but thinks

It's ashes from a childhood fire bombing.

On the far side of the Atlantic my stomach digests

Food that never passed through my lips

Food my teeth didn't chew

Food my tongue hasn't tasted

Food that could have made this spirit stronger

And act sooner if someone offered it to Dou Yi.

But my heart--

My heart beats in this town,

Pumping blood through a man

Loved by the son of an official,

A son who moved Heaven and Earth for

His Happiness.

His Future.

His New Harmony.

These offerings have given me strength

I feel my spirit reviving!

Justice.

Justice.

Justice.

Justice and burial for the widow Dou Yi

Justice.

Justice.

Justice.

But how can you bury a woman whose butchered body's still living?

Justice.

Justice.

That is my heart. It should beat inside me.

(Dou Yi thrusts her hand into Rocket's chest and retrieves her heart.)

Snow in MidsummerPremiered in2017

Snow in MidsummerPremiered in2017- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

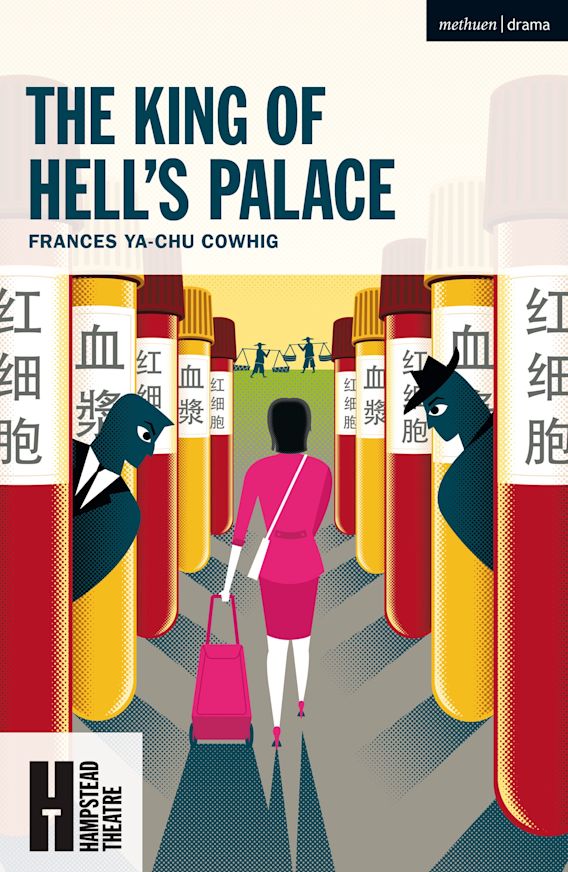

The King of Hell's PalaceA Play

KUAN

I’ll call out the license plate. Don’t settle for less than ninety thousand.

(Kuan steps onto the highway-----then is yanked back, as Wen lunges forward and pulls him to safety. The sound of the truck passing. Headlights fade. The brothers fight.)

WEN

I’d rather die a death of a thousand cuts than outlive my wife. I thought I could face it but I can’t. She wants me to be the strong one, but I can’t be. I can’t watch her die. Please don’t make me shame myself. Let me be a hero. If you go, I’ll wait for the next truck and follow you out of this world. Let her remember me as the man who fought for her until his last breath. Alive I’m worth nothing. Let my death buy my son medicine. Let my flesh feed our flowers. Some people have meaningful lives. Let my death have a meaning. Please, brother. Give this to me.

(Kuan steps aside. Wen stands on the edge of the highway and faces the approaching truck. He tries to step onto the road. His knees buckle. His body’s frozen in fear. Wen pounds on his legs with his fists.)

WEN

MOVE!

KUAN

You have life in you still. This isn’t your end.

(Kuan steps into the blinding headlights of an oncoming truck. LOUD, LONG HONK.)

KUAN

In the next life we’ll be a family again.

The King of Hell's PalacePremiered in2019

The King of Hell's PalacePremiered in2019- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Mary and the MonstersA Libretto

(Enter News Sellers.)

NEWS SELLERS

Three thousand Memphians fight for their lives

Blame the Black and Irish if you don’t survive

Epidemic’s ravaging our Bluff City

Death Cart wheels rattle through every street

In ghetto Pinch-Gut

Each house has caught the Stranger’s Disease

Caught the Stranger’s Disease

Extra extra come read all about it

Read all about it---

(Music darkens. The DEATH CART DRIVER enters.

He pulls a cart stacked high with DEAD BODIES

HIDDEN FROM VIEW by an oil cloth.

As he approaches the news sellers, they HOLD

SPONGES to their NOSES and FLEE.

The driver pauses outside Mary & George’s home.)

DEATH CART DRIVER

(Spoken)

Knock Knock

Mary and the MonstersPremiered in

Mary and the MonstersPremiered in

-

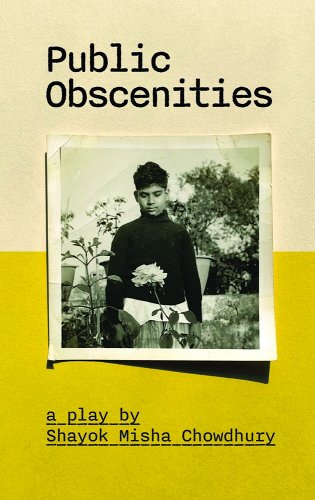

Public ObscenitiesA Play

CHOTON

I’m just saying like taxonomically, does it even make sense to categorize my genitalia and your genitalia as the same thing, like…

He indicates RAHEEM’s penis.

…if that’s a penis then…

He pulls his boxers down to show his own penis.

I mean what is this? It’s a polyp.RAHEEM

Okay.

CHOTON

It’s a little nunu.

RAHEEM

Well I like your little nunu…

RAHEEM examines CHOTON’s penis. He pulls back his foreskin just a bit. CHOTON winces.

CHOTON

Ow. Careful.

RAHEEM

What?

CHOTON

No it’s— it’s just sensitive.

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Public ObscenitiesA Play

CHOTON

You know that’s the only picture I’ve ever seen of him?

Chhobi hoye giyechhe…

RAHEEM

What’s that?

CHOTON

That’s what we say when somebody dies. Chhobi is picture.

RAHEEM

Shobi?

CHOTON

It’s the aspirated “chh” sound. Like “ch” then “huh”—

RAHEEM

Ch-hobi.

CHOTON

Yeah, chhobi hoye giyechhe. Has become a picture.

I mean that’s literally what he is now, right? Just like…that one picture…that after he died, somebody picked to get enlarged and framed and now…that’s the picture.

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Public ObscenitiesA Play

PISHE

You know I had one dream this like actually, some years back. Vivid dream. I am in a cinema hall…and on the screen, I am seeing one young executive…holding a portfolio…leather portfolio…entering a hotel room. And from that hotel room, through the window, can be seen a swimming pool. Ok? And in the swimming pool, he saw a beautiful looking girl. And this executive, he very much has a want to meet this girl. Then the shot changes. That girl is now sitting inside the room, wearing a green sari. And the girl says to him, I have a story to tell: when I was twelve thirteen years, I was walking by the river…suddenly a strong flood has come, and with my hands in the air like this saying save me, save me…then the picture faded. Then next scene is showing one elderly gentleman, wearing a dhuti. And until now actually shots were in color, ok? This one it became black and white. Elderly gentleman he is going, basket on his head…as he is going, absentmindedly like this, as if he is catching a fly and putting in the basket. Catching. Putting. And seeing this I turned to my friend and sayed— all this time there was no friend there, suddenly my friend was next to me— and I sayed to him: this is trash! This cinema has no meaning. And just as I sayed this, my sleep broke. And finding Pishimoni next to me, I sayed to her…what a strange and beautiful cinema I have seen. Just like this I sayed. “What a strange and beautiful cinema.”

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023

Public ObscenitiesPremiered in2023- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Skinship: StoriesFrom"Skinship"

By the end of the day, Ji-ho had moved things around, managing, even, to reposition an oak dresser by himself, whereas our mother and I, for all the years we would occupy the middle room, would never take down my cousin’s Star Wars poster, his Carnegie Mellon pennant. Every now and then, she and I would start up the same old argument about who slept on the floor and who slept on the twin bed. Each of us trying to urge comfort on the other. Neither of us knowing how to commit an act of selfishness.

Skinship : Stories

Skinship : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Skinship: StoriesFrom"Skinship"

“Hello, my name is,” my uncle coached. “Try it,” said our aunt. “Quickly now,” said our mother. Under the table, I pressed my leg against Ji-ho’s, communicating a tense warning if he dared laugh.

“Hello, my name is So-hyun.”

“Hello, my name is Ji-ho.”

“More louder,” our uncle said. “With confidence.” Row-der. Con-pi-densh. Suddenly, I was caught unprepared by the thought of our father. How he could do all the accents, use all the slang, say things like “shit” and “cash” and “I should be so lucky” with a touch of insolence.

Skinship : Stories

Skinship : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Skinship: StoriesFrom"Skinship"

I desperately wished that he, our father, could continue to be a silence, an absence, or even a faithless promise for some future time. But there he was. What would he do? What would he say? My brother, Ji-ho, wondered too. I could sense it in his quick, light, audible breathing. Our father took a step forward. He looked toward our mother. “Ja-gi-ya,” he said to her. This is a thing that Korean men call their wives. It is sometimes translated as “honey” or “sweetie.” But what it literally means is “you-yourself,” and behind that is still another meaning: “my-own-self.” And then he told her to move aside.

Skinship : Stories

Skinship : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Temple Folk: StoriesFrom"The Spider"

The hotel staff placed a pitcher of water on each table next to a small stack of translucent cups. I couldn’t help but shake my head at that. We would have been better off, I figured, taking Imam Saleem’s suggestion and just staying put at the Temple. The kitchen sisters would have at least given us some fruit punch and sugar cookies. Hell, had we asked nice enough, they might have made us some fried chicken and potato salad. If we were trying to throw money around like Rockefellers, why not put it in the building fund or pay zakat? But I was a one-man HVAC operation, with little more than a truck, some tools, and a house I was just three mortgage payments away from owning outright. As far as those brothers were concerned, I was too ordinary, based on outward appearances, to be an example.

Temple Folk : Stories

Temple Folk : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Temple Folk: StoriesFrom"Sister Rose"

When Intisar was small, she imagined that Sister Rose made her home in a mist of clouds enveloped all day in ethereal rays of light. She thought so because of the way Sister Rose seemed to float underneath her long abayas across the Musallah floor to the spot where she and five or so other little girls would gather for her Sunday school lessons. What else could explain her litheness, her sunset-peach skin, the way her irises sent threads of gold bounding out from the pupils like a million solar flares?

Temple Folk : Stories

Temple Folk : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop

-

Temple Folk: StoriesFrom"Nikkah"

Qadirah considered what he wrote and folded her arms. Until that moment, there wasn’t a single person she’d met on the platform that interested her, though a few keystrokes was all it had taken to feel drawn to this new presence. It must have been his adherence to the etiquette, not pushing her to violate the rules of modesty and video chat like all of the others, in addition to his unwillingness to be swayed or fooled—traits that reminded her of herself. In this recognition, she felt a likeness that warranted more forthrightness than she had previously shown.

“It’s Qadirah,” she replied finally. “That is my real name, if you must know.”

“Qadirah! The Capable! The Powerful,” he wrote back. “A very nice name, al-Hamdulillah. I understand why you wouldn’t tell me outright.”

Temple Folk : Stories

Temple Folk : Stories- Print Books

- Bookshop