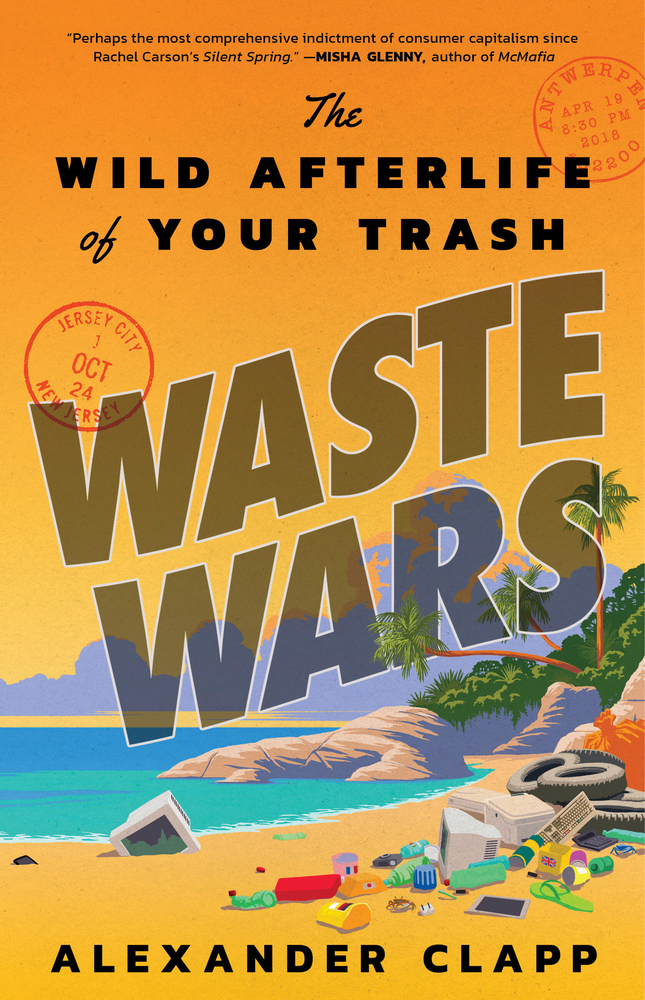

Waste Wars: A Journey Through the World of Globalized Trash

The project:

Much of what the world has thrown away for the past forty years — plastic water bottles, cell phones, rubber tires — has had a highly profitable and environmentally devastating second life, getting bartered, trafficked, and offloaded to the poorest places on Earth. Waste Wars is an exposé of this business: how it began, how it destroys the environment, and — most importantly — the international rivalries it has brewed and continues to brew between the "developed" and "developing" worlds.

From Waste Wars:

The dirt ribbon of track plods deeper into the peninsula in Accra’s Korle Lagoon, beyond the smartphone dismantling stations, towards more complicated technological autopsies. Some fifteen feet across, the path is an unrelenting vehicular quagmire, juddering with motorized tricycles and pickup trucks and retrofitted tractors and choking with their commingling exhausts. Every morning, they ferry hundreds of tons of mangled appliances — ceiling fans, washing machines, motorcycle engines, refrigerators — into Agbogbloshie, a vast scrapyard and slum home to some 40,000 Ghanaians; every afternoon they motor some of the world’s most precious materials — cobalt, copper wiring, gold — out, a ten-hour turnaround that extracts valuable material and leaves little behind save a hazy mass of pollution. My feet crunch over shards of computer-screen glass and cracked iPad covers and stray Hewlett Packard mice; a pink bra has been stamped into the mud by so many thousands of footsteps that it resembles a fossilized crustacean.

Itinerant barbers bearing white plastic stools roam around doling out buzzcuts for ten cedis, or a buck. Women shimmering in tribal dress meander through the morass, selling juices out of plastic laundry bins. The constant clank of hammers laying into electronics pulses across the slum like a heartbeat. Clank! Clank!

About halfway down the peninsula, the appliances that have arrived on those motorized tricycles and pickup trucks are being broken down into pieces. Hundreds of young men — known in Agbogbloshie as the “dismantlers” — sit in circles straddling gutted microwaves and computer monitors. Most are wearing knee-length colored dress socks and open-toed sandals, which poke out of great rats’ nests of electrical wiring. The dismantlers have one job: for eight to nine hours a day they pound their fat gavel hammers into old ceiling fans, motorcycle mufflers, speaker systems. The work has a factory-line monotony to it, only it is the exact opposite of assembling. It is a de-manufacturing line, reducing all the amenities of our modern world — the air conditioners that keep us cool, the refrigerators that preserve our food, the motors of the lawnmowers that cut our grass — back into their constituent elements. The juxtaposition never ceases to be jarring: the work of the dismantlers may be pre-industrial and backbreaking, but what lies beneath the strokes of their hammers is some of the world’s most advanced technology. And while streamlined automation might have manufactured these products, human labor remains the most efficient way to get rid of it.

The grant jury: A visceral, jaw-dropping inquiry into a vital climate vulnerability — "our planet’s runaway garbage pandemic” — that is easy to ignore but implicates us all. Alexander Clapp blends impressive on-the-ground reporting with strong narrative drive, a lively turn of phrase, and gripping characters. In this plunge into the often corrupt world of modern manufacture, consumption, and destruction, Clapp takes extraordinary personal risks to explore places on the planet where few wish to go, or want to acknowledge.

Alexander Clapp is a journalist based in Athens, Greece. He is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books, The New York Times, and The Economist, among other publications.

Selected Works