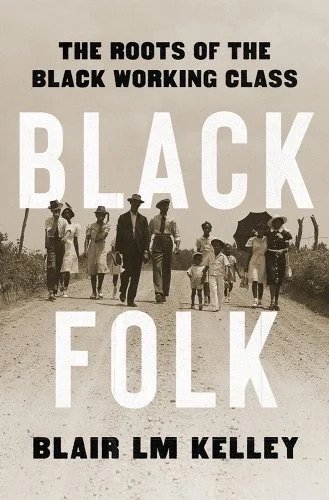

Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class

The project:

Any attempt to understand America’s working class must begin with the history of Black folk, who have historically been the most active, informed, and impassioned working class in America. Tracing the story of the Black working class from first emancipations to the essential workers of our COVID-19 present through family stories and traditional sources, Black Folk describes the connection between the everyday lived experience of working Black people and their labor and politics.

From Black Folk:

Enslaved Black people built a new faith way, one that at first glance runs parallel to that of their oppressors, but it was marked by fundamental differences. Their new churches would put them, the downtrodden, at the center of the story.

One worshipper recounted that when they would gather to sing and pray they would “take pots and put them right in the middle of the floor to keep the sound in the room… [to] keep the white folks from meddling… the sound will stay right in the room after you do that.” The overturned pot was a remnant, a piece of an African faith, perhaps a symbol of a forgotten deity or part of a holy ritual. The details were lost, but a sense of its power for the faithful remained. The overturned pot helped to make the hush harbor both quiet and holy, imbued with the authority of their old faith to protect them as they worshipped in a new way.

One former slave minister, Peter Randolph, recounted that “the slaves [would] assemble in the swamps out of reach of the patrols.” Guiding each other by “breaking boughs from the trees, and bending them in the direction of the selected spot,” they would meet at an appointed time. Randolph described their worship:

They first ask each other how they feel, the state of their minds… Preaching in order… then praying and singing all round, until they generally feel quite happy. The speaker usually commences by calling himself unworthy, and talks very slowly, until, feeling the spirit, he grows excited, and in a short time, there fall to the ground twenty or thirty men and women under [the spirit’s] influence. Enlightened people call it excitement; but I wish the same was felt by everybody, so far as they are sincere. The slave forgets all his sufferings, except to remind others of the trials during the past week, exclaiming: “Thank God, I shall not live here always!” Then they pass from one to another, shaking hands, and bidding each other farewell, promising should they meet no more on earth, to strive and meet in heaven…

Even as more laws designed to stifle Black gatherings were put in place, the desire of the enslaved for congregation grew. In their secret gatherings new leaders were born: those who could minister, those who could sing, those who could lead others to faith or to freedom. After Emancipation, these congregations became their first Black collective spaces. The fights for education, mutual aid, the battle to govern and to gather together both in and out of faith, began in those churches that started without walls. Those hushed conversations provided a guide for how the newly freed working women and men would seek out righteous ways of figuring out the cost.

The grant jury: Timely, necessary, and loving, this is an authoritative and groundbreaking work that serves as a corrective to longstanding ignorance about the Black working-class. The project of interpreting the rich landscape of their lives and politics is revelatory and long overdue. Few academics can write in such a clear, captivating voice. Kelley’s characters shine and her insights pop; she writes with an urgent sense of time and place, bringing human scale to a major moment in American history. This shows every sign of becoming a seminal work that our children and grandchildren will still be reading.

Blair LM Kelley is an assistant dean and associate professor of history at North Carolina State University. Her first book, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship, won the Letitia Woods Brown Best Book Award from the Association of Black Women Historians. Active inside the academy and out, Kelley hosted her own podcast and has been a guest on MSNBC’s All In and NPR’s Here and Now, and she has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and NBC’s Think. She lives in Durham, North Carolina.

Selected Works