I’m a bit unsure of why I’m up here on this dais, but now that I am we’ll get on with it, catch-as-catch-can. Which is to say that finding myself participating in a ceremony during which so many gifted writers are to be presented the Whiting Foundation’s prestigious awards is intimidating. For while most writers exercise their craft isolated in shadows, and do so out of their dedication to art, the efforts of tonight’s winners are being recognized in public, and that alone endows this occasion with an aura of dreamlike fulfillment.

I’m reminded of something that Robert Penn Warren once wrote about the challenge which the Founding Fathers left future Americans to solve when they committed to paper the democratic ideals upon which this nation was founded. In a sense the Constitution and Bill of Rights made up the acting script which future Americans would follow in the process of improving the futuristic drama of American democracy. The Founders’ dream was a dream of felicity, but those who inherited the task of making it manifest in reality were, alas, only human. Not only do Americans spring from different geographical areas, but they possess – and are possessed by – a variety of conflicting attitudes, personal, social and regional. What’s more, since the revolutionary days of its founding, this nation has grown so rapidly and transformed its landmass so chaotically that frequently we don’t know where we are or where we’re headed. In reality, the media, especially television, that facile transmitted of composite images, has further increased our confusion – and this despite the fact that it also provides us with copious details from the past that charm, delight and instruct us.

Of such matters we’re all aware, but tonight’s occasion makes me realize once again how important it is that the United States continues to have writers, such as tonight’s winners, who make the most of their personal experience. The Founding Fathers conceived this nation as a collectivity of individuals who, ideally, are united in their diversity. We are one and yet many, an ambiguity that involves our personal identities no less than it gives shape to our politics. Thus, given the zigs and zags of our country’s development, it is imperative that we keep the responsibility of achieving our individuality always consciously in mind.

Under the pressure of our nation’s unresolved issues from the past and the rapidity with which technology is changing the modes of our living, the conflict between our national ideals and everyday reality is constantly increasing in intensity. This combination of forces increases our American tendency toward historical forgetfulness as we move toward and away from our national ideals. Deny it or not, we live simultaneously in the past and the present, but all too often while looking to the future to correct our failures, we pretend that the past is no longer with us.

Our national tendency to ignore or forget important details of our past reminds me of the philosophical stance of certain adults with whom I hunted during my boyhood in Oklahoma. After bringing down a rabbit or quail, men would proclaim in voices that throbbed with true American optimism, “A hit, my boy, is history!”

But if they missed and the game got away, they’d stare at the sky or cover and say, “A miss, my boy, is a mystery.”

Well, in this country there have been many hits that are now attributed to the success of our democratic ideals. On the other hand, there have been misses in our attempts to achieve our democratic commitments that are so embarrassing that we have a tendency to assign our failures to the world of mystery./span>

Actually such failures spring from our confusions of motive and misguided efforts, which too often we try to sweep under the rug instead of addressing their consequences forthrightly. This, I think, is one of the implicit functions of American writers. Whether they be poets or novelists, essayists or dramatists, they are challenged to take individual responsibility for the health of American democracy. It is their role to transform the misses of history into hits of imaginative symbolic action that aid their readers in reclaiming details of the past that find meaning in the experience of individuals.

At any rate, such ideas came to mind recently when I began reading a book which its author was kind enough to send me. This book, titled Old Abbeville: Scenes of the Past of a Town Where “Old Time Things Are Not Forgotten,” is a history of old Abbeville, South Carolina, which you might recall as the birthplace of the national conflict over slavery, the war which is known in the South as War Between the States. It was also the home of John C. Calhoun and General Sam McGowan, one of General Robert E. Lee’s lieutenants and later the chief justice of South Carolina. The author of Old Abbeville is Professor Lowry Ware, a historian emeritus of South Carolina’s Erskine College.

Somehow in poking into the mysteries of his native state’s history, Professor Ware discovered that I too sprang from South Carolina via my father, who was born and grew up in old Abbeville. In his scholarly research Professor Ware came across information about my grandfather that I found so unexpected that I erupted with laughter. While I had met my grandfather during the fourth year of my life, I had known him best as a mute patriarchal figure who stared from the wall in an old photograph. But now he had been brought so vividly to life in printed word on a page that I felt I’d been given a view of the mystery surrounding my roots.

Even more startling was the fact that the book had been written by a white South Carolinian. Thus I discovered a thread of my parental background snarled in the national tragedy which came close to destroying this nation but which left it drawn closer, if most contentiously, together. My reaction at finding my personal connection with slavery and emancipation states in words was such a mixture of tragedy and comedy that it filled me with a blueslike laughter which caused my wife to ask what had come over me.

What had come over me was Professor Ware’s research into my activities during the Reconstruction. My laughter was ignited by learning that the man I knew as Grandpa was known in the town and surroundings as “Big” Alfred Ellison. Professor Ware then revealed that my grandfather had been a slave of the Reverend M. A. Ellison, who was pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, and that my grandfather and his brother, William Ellison, “become freedman in Abbeville in 1865.” According to Professor Ware, “the latter was, or soon became, educated and he served as a schoolteacher during the Reconstruction and later. Alfred never learned to read or write, but his strength of body and character led to his appointment was town marshal in the spring of 1871 and enabled him to keep that position for most of the next seven years.”

The Press and Banner, a local newspaper, “often made favorable comments on [Big Alfred’s] service to the town. For example, on January 5, 1872, it noted, ‘The peace of the village and the harmony of Christmas week were broken by two shooting scrapes …. John McCord, who had been arrested by Alfred Ellison, the town marshal, resisted the officer and discharged his pistol without effect, however, upon the marshal, who knocked him down, giving him a serious blow.’

“On August 5, 1873, [The Press and Banner] reported on an altercation between Arthur Jefferson, a black country commissioner, and the marshal, when the former was ‘using a few more expletives than the marshal thought proper. Ellison, who is a powerful man, immediately disarmed Jefferson and threw him down, without any particular regard as to which part struck the floor first …. Alfred is usually able to take care of himself.’

“The Press and Banner on September 20, 1876, following a town election in which the white Democrats regained control of the local government, declared that ‘the election of the town marshal takes place on next Monday. We think justice and our best interests as a town demand that a coloured man get the place.’ A week later, it reported that Alfred Ellison was re-elected.”

Ladies and gentleman and my fellow followers of the writer’s trade, I hope that what I’ve read from Old Abbeville has given you an idea of the living texture of human relationships that existed in the South during that turbulent phase of our history, and a better sense of the humanity of ex-slaves like my grandfather and his brother William. To that end I’ll bring this closer to our own times by reading the following:

In later years, Alfred Ellison took part in local Republican meetings, and in 1895 he testified before a Congressional Investigating Committee which was concerned with alleged irregularities in the election between Republican Robert Moorman and A. C. Latimer, Democrat. [Sounds like today!] Cross-examined by Coleman L. Blease, Latimer’s attorney and later governer of South Carolina, Ellison’s testimony in part was: “Abbeville is my precinct. Been here nearly all my life. I voted. I registered. I had trouble in registering. I applied on the first Monday in April, but got one in May by paying 25 cents for an affidavit. I got the registration ticket but had to wait, on account of the Supervisor of Registration not doing his duty …. He waited on ten white men and more, and I standing there holding my affidavit ready for him to register me. I was there between give and six hours, waiting …. No trouble for white men to get registration tickets. Colored men had trouble …. I voted for General Hampton in 1876, but I am not a Democrat.”

The point that Big Alfred’s grandson makes of all this is that the past still lives within each of us and repeats itself with variations. Looking back, you feel the pain we’d like to forget because of its tragedy, but if we’re to survive and get on with the task of making sense of American experience, we’ll view it through the wry perspective of sanity-saving comedy. Incidentally, Professor Ware’s research reveals that there are still existing records of more socializing between the white slave owners, freeman and slaves than even Faulkner has told us about, and I don’t mean merely in the dark. There also were interracial parties that became the source of recriminations aired during political elections, which is another example of the mixture of past and present.

I’ll close by reminding my fellow writers, as I frequently remind myself, that you’re doing far more than creating interesting tales based on your individual view of the American experience. Underneath your efforts you’re helping this country discover a fuller sense of itself as it goes about making its founders’ dream a reality.

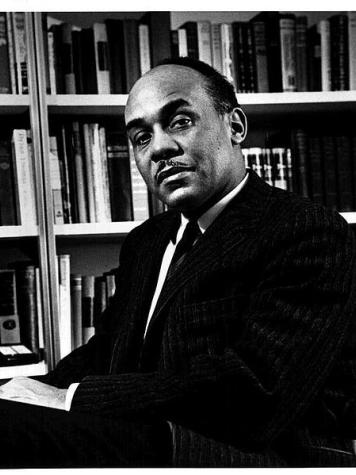

Ralph Ellison (1914–94) was born in Oklahoma and trained as a musician at Tuskegee Institute from 1933 to 1936, at which time a visit to New York and a meeting with Richard Wright led to his first attempts at fiction. Invisible Man won the National Book Award. Appointed to the Academy of American Arts and Letters in 1964, Ellison taught at several institutions, including Bard College, the University of Chicago, and New York University, where he was Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities.